The Black community in the United States has always been a racial minority and a lack of representation on campuses such as SJCC is no different.

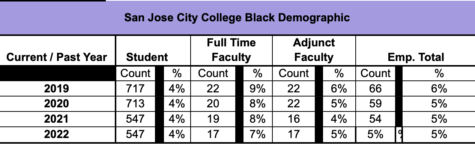

The number of Black students and Black employees at SJCC have decreased by around 200 between 2019 and 2022, according to internal demographic documents provided by Xao Yi, a human resources representative. There were a total of 436 campus employees in 2022, and only 27 of those identified themselves as Black or African-American.

“The percentage of African-Americans has consistently dwindled, for the most part, over the last 10 years,” said Dedrick Griffin, an African-American professor who has taught English for 13 years. Griffin noted that he typically sees one or two Black students on average each semester taking his courses.

Dr. Kahlid White, who remarked that he is the only full-time African-American Studies Professor at SJCC since 2008, shared that Black people – and especially Black men – are typically seen as potential athletes and entertainers, which often leads to degradation of their perceived societal value. He further expressed frustration that oftentimes African-Americans aren’t typically considered intelligent enough for leadership positions.

For White, there is a certain level of irony to this, “Africa started higher education. [It] comes from [Africa], [and it] comes from us,” he said.

Making A Difference

Griffin shared that in some cases many instructors who are not African-American may feel less comfortable approaching Black students because they are not aware of how and when to speak to them.

“I don’t think there’s a full understanding of the experience of people-of-color because it’s difficult for people to know what that experience is like unless they’ve gone through it themselves,” Griffin said.

Griffin later explained that this racial divide can inadvertently create a distance between such professors and students, an occurrence that rarely happens between a Black professor and Black students.

“There’s a [certain] type of understanding,” said Carol Easter, an art instructor who has been teaching for 10 years.

Griffin said that he takes notice when a Black student is in his class. He shared that for him, it’s not that Black students are given special treatment, but that they are “seen”.

It’s not just a one-way feeling either. African-American students in his classes often reciprocate – they take notice of a Black professor, he said.

“If we continue to have an environment where we don’t see ourselves then that will set limitations for our children,” Griffin said.

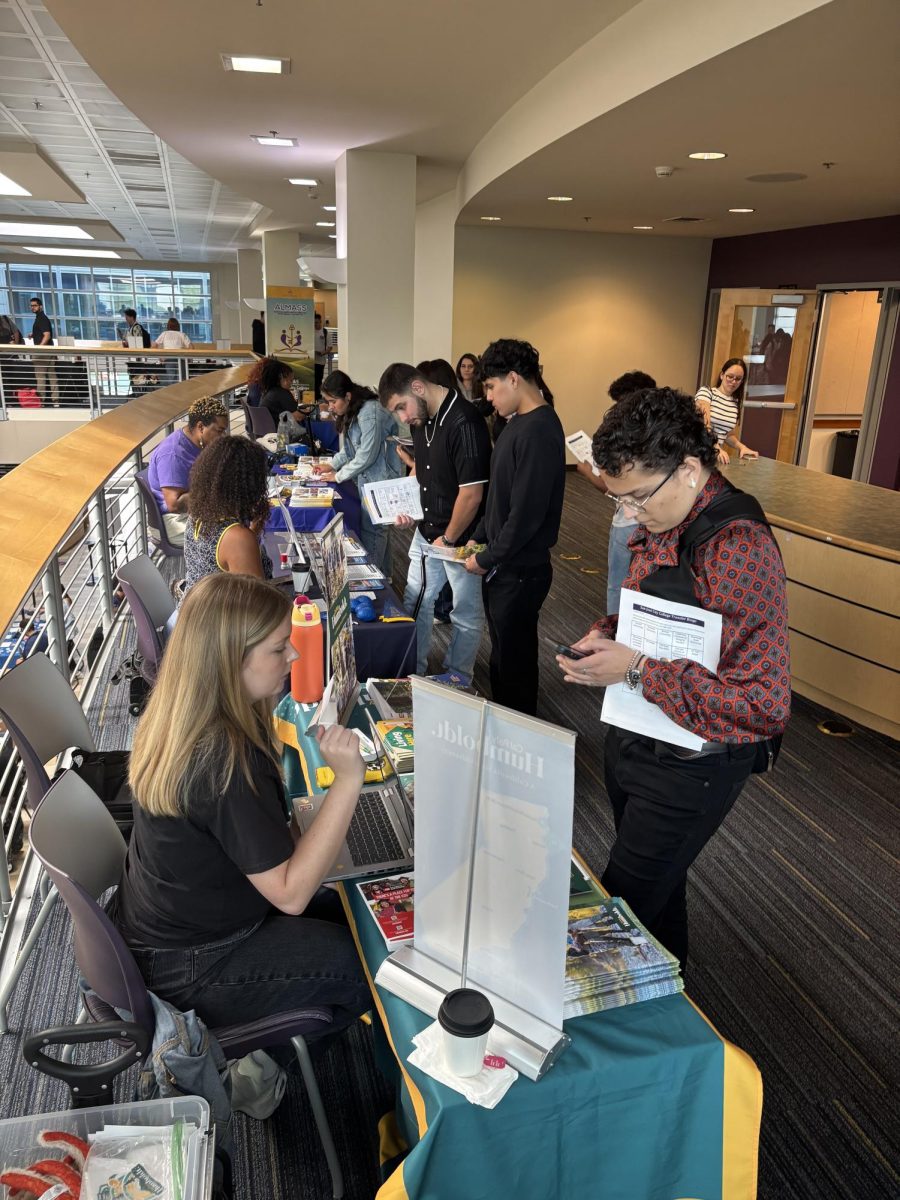

SJCC has resources, clubs and programs that they offer to students and staff of color.

One club is Umoja – a community program coordinated by Griffin at SJCC designed specifically for students of African ancestry, and honors Black students with events centered on intellectual and cultural traditions of the African continent and the African-American diaspora.

“I would say the school has done a lot to support the Umoja program and support the idea of diversity, equity and inclusion,” Griffin said.

Still, Griffin believes more could be done for Black students, and he remains committed to encouraging the school to better their outreach to its African-American students.

Big Issue, Slow Progression

White shared that those who are not Black can choose not to care or concern themselves with issues involving race, but Black people don’t have such privileges. He further explained that the campus is not prioritizing Black students, Black professors and other Black faculty members.

“It’s a very anti-Black system on a very anti-Black campus and a very anti-Black district and a very anti-Black higher education system,” White said.

White recently performed a research study, Black Voices from the Ivory Tower, in hopes of reaching out to white faculty and administrators, as well as staff from other racial background to be allies.

“We need some of those people as allies in our fight to get the equity, the justice and the inclusion that we so desperately deserve,” White said.

Easter, despite other professors voicing their concerns, said she still appreciates the resources SJCC has to offer and remains optimistic going forward.

“Being African American, and the African American experience, can be defined as a resilience,” Easter said.