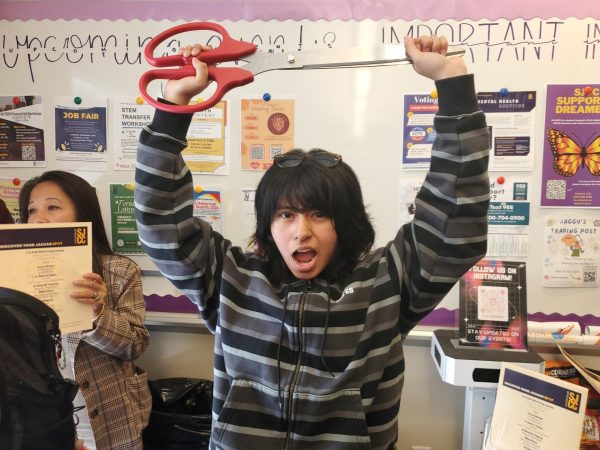

“Sí se puede, on three!,” commanded San Jose City College President Rowena Tomaneg on Oct. 10, at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Sí Se Puede program’s new center.

On either side, she is flanked by a cadre of the school’s most senior officials, a group that includes District Chancellor Beatriz Chaldez and Vice President William Garcia. Ixta Bautista, a double major in Architecture and Environmental Engineering, is to her left, holding a pair of comically oversized red scissors.

“One, two, three. Sí se puede!,” the group shouts.

Bautista cuts the ribbon standing in front of them, eliciting a deluge of jubilant applause from everyone in attendance.

The ceremony, attended by over three dozen students and staff in M-106, celebrated the latest step forward in bringing the school’s nascent Sí Se Puede program to full fruition, which hopes to academically support hundreds of first-generation Latino college students over the next five years. Six people, including Tomaneg, Bautista, Chaldez, and Garcia, gave remarks.

Sí Se Puede, which takes its name from the now-iconic slogan of the United Farmworkers, says on its official webpage that it offers things such as free textbooks and counseling to first-generation Latino college students, which the school defines as Hispanic-identifying students whose parents haven’t gone to college in the United States. According to Joyce Lui, SJCC’s Dean of Research, Planning, and Institutional Effectiveness, the program currently serves 167 out of the college’s roughly 11,000 attendees.

The program, funded by a $3 million Title V grant from the U.S Department of Education, is part of a larger, nationwide effort by the federal government to put money in the hands of colleges that serve predominantly Latino communities, who are often the victims of broad systemic barriers that leave them less likely to complete college.

San Jose, which boasts a substantial Hispanic population, is far from immune to the issue.

Recent data from the U.S Census indicates that only 21% of Latino-identifying individuals in Santa Clara County reported attaining a Bachelor’s Degree, compared to 55% of the county overall. School administrators say that Sí Se Puede is designed to help address that disparity.

“We have identified gaps in terms of what we can do better to serve our students and our community. I am very confident this grant will help,” said Vice President Garcia, with an excitement that many others present also shared.

Bautista, in an improvised speech that she, according to her, was “sacrificed for” by her peers, said that the program is not only “important to help students [but also] to influence students into thinking of things they wouldn’t have thought about yesterday.”

“How many of you guys can say you got here by yourself?,” she asked the crowd, to which there was no response.

SJCC’s Dean of Academic Success and Student Equity, Rene Alvarez, a senior school official who played an instrumental role in writing SJCC’s grant application to the Department of Education and also oversees Sí Se Puede, gave the event’s closing speech, which came directly after Bautista finished speaking.

In his remarks, he recalled telling his father about the program, who told Alvarez that it reminded him of when he himself first immigrated to the United States and being part of a tight-knit group of five families that would mutually support each other through hardship.

“That’s exactly what this is,” Alvarez said, as he became visibly emotional, appearing to wipe tears from his eyes. “Having something like this when I was coming up would’ve been transformative. [These] things didn’t exist back in my day.”