Composite images by Mark Sheppard

Composite images by Mark Sheppard

A few commit it. Some know those who have. Others have never even heard of it.

Financial aid fraud steals from San Jose City College and other college campuses nationwide.

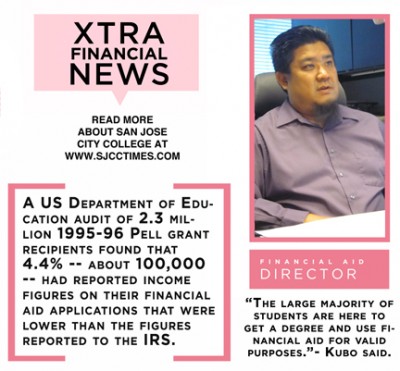

“It has gone on before, and I think it will continue,” said Takeo Kubo, director of financial aid at SJCC. “In short, yes, (financial aid fraud) does need to be resolved.”

Some students commit financial aid fraud by reporting false financial information for themselves or their families, or by signing up for classes with the intention to drop once they receive their financial aid.

Manuel Garcia, 28, a psychology major, said he overheard a classmate say, “I just got my financial aid, and I won’t be coming back.” The student never returned to Garcia’s class.

“Some students sign up knowing they will drop, not knowing they have to pay back (the financial aid money),” said Felicia Segura, 19, an administration of justice major who works in the Financial Aid office.

However, a loophole enables some tricky students to keep financial aid money without the demand for pay-back.

“If (students) have gone through a certain portion of classes without dropping, they are able to keep everything without having to pay anything back,” Kubo said.

Kubo said that the financial aid office does not track how students spend their financial aid money.

“(They may) stay here as straight-A students or leave immediately and just run away with the money,” Kubo said.

Financial aid recipients are required to maintain satisfactory academic progress, including maintenance of a 2.0 GPA and completion of 75 percent of attempted classes. SJCC calculates the required academic progress once per year.

“If students sign up for full loads of classes, receive financial aid and then drop all the classes with the thought of ‘I got paid so I’m going to buy myself something or take a vacation,’ they might be able to do that for a semester or two, but eventually it will catch up to them because they are not maintaining academic progress,” Kubo said.

Financial aid is defined by Kubo as something to help cover the cost of education. That includes tuition and fees, books and supplies, room and board, transportation and some miscellaneous expenses.

Computer programming major Davicia Tautai, 19, who works in the financial aid office, said students request aid for other reasons.

“I’ve heard, ‘I need my money; I need to pay my bills’; ‘I’m not registered at this school, but I’m in debt,’” Tautai said.

Tautai said she has also heard students threaten and curse at workers in the financial aid office.

Financial aid fraud can become a bigger expense for taxpayers when multiple criminals form a fraud ring.

According to a document released by the Board of Education Office of the Inspector General on Sept. 18, a fraud ring is made up of “large, loosely affiliated groups of criminals that seek to exploit distance education programs in order to fraudulently obtain student aid.”

The document also revealed the indictments of criminals Brent Wilder and Michael Huddleston, who between 2009 and 2012 “caused the fraudulent disbursement of more than $200,000.”

The two employed more than 50 students to apply for financial aid at American River College, Sacramento City College and Consumnes River College.

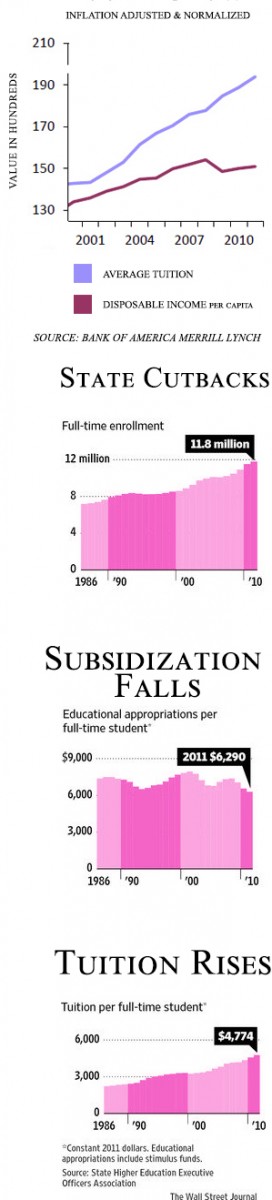

According to the OIG document, community colleges tend to be more susceptible to financial aid fraud because tuition costs less, leaving a greater award balance intended for other educational expenses.

Robert Thomas, 42, a drug and alcohol counseling major, said he has heard of the homeless receiving financial aid from multiple community colleges simultaneously.

“I lived at a homeless shelter, and the information trickles down,” Thomas said.

Kubo also said that students are able to receive aid from multiple campuses. But that ends when students either run out of money or schools begin questioning them.

“There is a national database that tracks a student and how much financial aid he receives at any college in the United States … you can tell after a certain point in the year if a student received financial aid, including student loans, at other colleges,” Kubo said.

There are some students who receive financial aid and continue taking classes, although Kubo questions their actual financial need.

“I raise an eyebrow when financial aid students are driving nice cars and wearing designer clothes,” Kubo said.

Students are reacting to illegitimate financial aid recipients.

“It affects the students who are really trying to go to school,” Thomas said.

“I live with my parents, but they aren’t paying for anything. I’m not getting any help,” Guzman said.

Though Kubo remembers students who committed financial aid fraud when he was in school and thinks students will continue to do so, he said he tries to focus on the majority of students at SJCC.

“We concentrate on the mass of people doing things right,” Kubo said. “Our efforts are better spent there.”